Council members and advocates debate changes to salary disclosure law

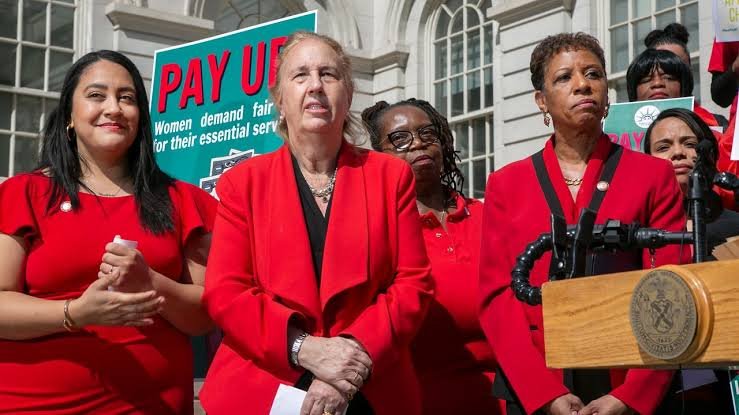

Business group leaders and advocates for pay equity sought to sway City Council members in a hearing Tuesday on the fate of a proposed bill that would significantly alter an existing law requiring that businesses include salary ranges in job postings.

The law, Local Law 32, passed the council late last year, and is set to go into effect in May. Advocates for the law have said it would help further eliminate pay gaps, especially for women of color.

Yet two council members have put forth a bill that would amend the existing law, with key changes: It would not apply to businesses with fewer than 15 employees, and exempt job descriptions for general hiring unrelated to a specific position, as well as jobs that can be done remotely.

JoAnn Kamuf Ward, a deputy commissioner for the city’s Commission on Human Rights, which addresses complaints and educates businesses on city employment rules, said that the exemption for general job postings, in particular, “has the potential to swallow the rule.”

“There’s the potential that an employer can just have an open… ‘We are hiring,’ and they might know the salary range, but they can use the potential carve-out to evade showing a salary range,” Ward said.

She added that the commission could work with council members to tighten the proposed legislation to avoid such cases.

“With both the existing law and the proposed legislation, the commission would only have enforcement power for roles being done by people living in the five boroughs,” Ward said.

The hearing was heavy on public testimony and light on council member participation, with only the committee chair, Nantasha Williams, and three other members — Rita Joseph, Amanda Farías and Gail Brewer — asking questions.

Williams is a co-sponsor of the legislation that would change the existing law, alongside Justin Brannan, who represents southwest Brooklyn.

The existing law, advocates say, if left untouched would help the city close gender pay gaps. For every dollar earned by white men, white women earn 84 cents; Asian women earn 63 cents; Black women earn 55 cents; and Hispanic women earn 46 cents, according to a 2021 City Council report.

The report concluded that the pay gap stems primarily from segregation between occupations that pay differently since the pay gap shrinks dramatically when comparing people of different genders and races in the same roles.

But business advocates suggested that the proposed legislation to alter the original law was necessary to avoid undue burden on small businesses.

Those companies are dealing with residual debt from the pandemic in many cases, Jessica Walker, the president of the Manhattan Chamber of Commerce, said in the hearing, and are facing stiff competition for workers in a labor market with historically low unemployment.

Williams said in her opening statements that she was “amenable to changes” to the legislation based on testimony. Yet in her questioning she expressed doubt that the existing law would eliminate pay gaps, in part because it wouldn’t mandate that private companies disclose all of their salaries.

“I don’t think this bill intends to erase salary inequity,” she said.

“There’s no way to know what a white person is making at a company through the salary ranges being on a job description.”

Advocates for pay equity who joined the hearing for public testimony disputed that point, pointing to studies that suggest that pay transparency in job advertisements does just that.

One recent study found that when one job search site, Hired.com, pre-filled the salary ask of a job searcher with the median salary offered for the position they were applying for, it eliminated the gap between how much compensation male and female candidates asked for.

Studies from other countries have also shown that increased transparency of salaries reduced gender pay gaps.

Julia Elmaleh-Sachs, a plaintiff’s employment discrimination attorney at Crumiller P.C., suggested that the remote work change in the proposed legislation also represented a significant loophole for businesses.

“An employer could say that their job posting refers to in-person work or remote work, which would allow them to not post a salary range,” she said.

Exempting businesses with five to 15 employees would eliminate protections for nearly half a million workers, including 222,000 women, said Debipriya Chatterjee, a senior economist with the Community Service Society.

State Sen. Jessica Ramos, joining the hearing during the public comment section, said that she opposed the proposed legislation in part because companies with up to 15 employees can still be profitable, and engage in wage discrimination.

“Whether you are a microbusiness or startup, pay discrimination should not be a tool available to you to scale your business,” Ramos said.

Business leaders and owners pushed for the new legislation. Kathryn Wylde, the head of the business advocacy group Partnership for New York City, said that May was too early to implement the disclosure requirements.

“Employers generally are anxious to support pay equity laws,” she said. “But we think the time to inform them just isn’t there, and to educate them on compliance.”

Wylde also suggested that, under the existing law, businesses could face litigation if they offered a candidate substantially more than what they advertised in the job posting, such as to bring someone in from another state. The existing law requires only that businesses post a “good faith” estimate for the salary.

“So this is an invitation to lawsuits, so that’s the concern that both large and small businesses have,” she said.

Barbara Kushner, the owner of a construction firm that has offices in New York and three other states and has worked on projects worth over a billion dollars, said that posting salary estimates could lead to her competitors offering higher salaries to candidates than she can afford.

Kushner said that she had recently posted a salary range in advertising for a company comptroller — $90,000 to $125,000 — in part because she didn’t want people to think she was acting discriminatively.

At the same time, she said, she looked for applicants’ qualifications before she took their salary requests into account.

“A salary range will only do so much for an employer,” Kushner said.

The proposed legislation, with only Williams and Brannan as co-sponsors, has not been scheduled for a vote, according to a representative for the City Council.